| | NEWS

A factual, firsthand report of the events of the infamous "Kristallnacht", November 10, 1938

by Rabbi Selig Schachnowitz

A Jewish store in Berlin after Kristallnacht

Translated from the German by M.L. Mashinsky

This was first published in 1992, 31 years ago.

Yated Ne'eman is proud to be the first to publish this firsthand account of the day after Kristallnacht in Nazi Germany. Written by a professional, it presents a stunning picture of the suddenness with which the events took place, reminding us that we can never truly know what the next day will bring.

Writing in November 2023, these events seem very close.

For Part II of this series click here.

The following is an eyewitness account of Kristallnacht, November 10, 1938, written by Rabbi Selig Schachnowitz, editor of the famous German Jewish weekly, Frankfurt Israelit, from 1908 to 1938. Though written as if about someone else ("Herr Bloch"), the main character is clearly Rabbi Schachnowitz himself.

Historical Note: On November 7, 1938, Herschel Grynszpan, a Polish- Jewish youth, shot and severely wounded Ernst Vom Rath, a German official, in retaliation for his parents' deportation to the Polish border. Vom Rath died on November 9, setting off riots in Germany (actually organized by the Nazi government). 191 synagogues were burned, thousands were arrested, hundreds wounded or killed. The tons of broken glass somehow inspired the name "Kristallnacht."

Rabbi Selig Schachnowitz

Born in Lithuania, and a talmid of R' Yitzchok Elchonon Spektor, Schachnowitz was a Swiss citizen, and could have fled Germany to safety long before. However, he chose to stay, since his newspaper served as an organ of vital information for German, Austrian and in fact, for all of European Orthodox Jewry. It is heart-rending to read the last few issues of the Israelit: The most recent punitive edicts for the Jews of the Reich; how to apply for emigration to Uruguay, or Costa Rica, or Bolivia; how to reach relatives, when letters to them had been returned "address unknown"; how to cope with the unimaginable...

After fleeing to Switzerland at the last possible moment, Schachnowitz continued his communal work, helping the Jews interned in refugee camps, spreading a message of faith and courage to those who felt that the world had abandoned them. His lectures are still remembered by many for their Torah-true message of encouragement, always leavened by a gentle touch of humor.

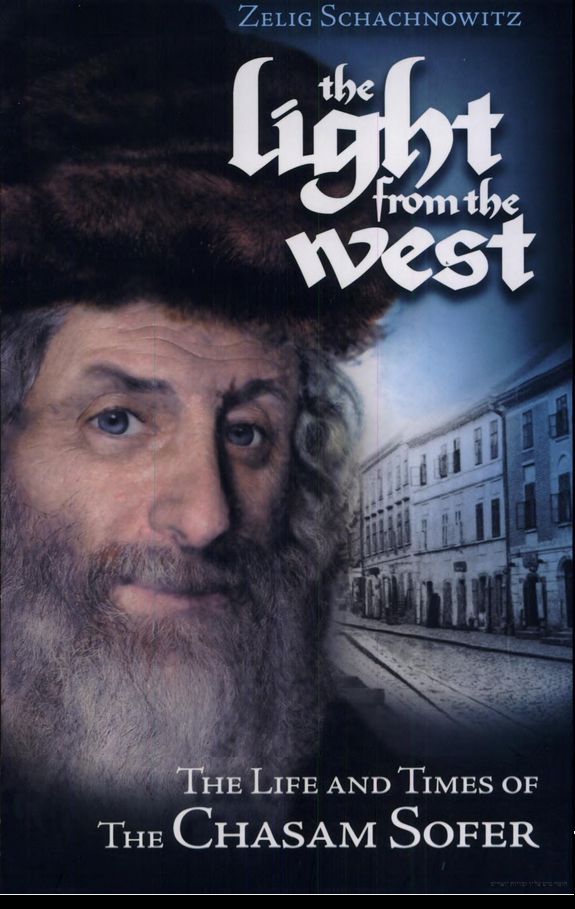

He continued to write. Among his many books, the following are available in English translation: Fire in the Sky, Light from the West - the story of the Chasam Sofer, and Avrohom ben Avrohom about the ger tzedek the Graf Potocki. His numerous articles helped to bring the world's attention to the plight of the Jews crushed by the Nazi regime. R' Selig Schachnowitz lived to see the defeat of the German hordes; his written work gives a true picture of Jewish suffering and heroism.

One of Rabbi Shachnowitz's books

To Distinguish Day From Night

At 6 in the morning, Herr Bloch awoke from a restless sleep beset by nightmares. He opened the blinds, but the pale morning light was blocked by fog. There was something heavy and oppressive in the air of the street below which was just beginning to come to life that prevented him from shaking off the foreboding caused by his dreams...

Salo Bloch was a sober and realistic man who did not believe much in dreams. But today there were no facile natural explanations to remove the heaviness from his heart, the feeling of something dreadful about to happen. True, the paper he had read last night before going to sleep had brought news of the assassination in Paris and of the sinking condition of the victim. If he should die the consequences here, in Germany, would be dreadful.

Depressed though he was, he dressed rapidly. He had to get out, fast, before the rising waters cut off his last chance of escape.

For the past thirty years, Herr Bloch had taken the same ten minutes' walk to the same synagogue, one of the most beautiful buildings in the ancient town, with its gray marble facade and its picturesque gables and domes. Today he took the newspaper from the mailbox before he left, and there, at the top of the page he found the item he feared: the name of the victim, with a cross next to it!

So it was all over now, he thought. Perhaps it would be wiser to stay inside today? Who knew what the rabble might do now?

But the street seemed as usual today. In the bakery across the street, hands moved busily under the dim light, shaping the day's loaves and rolls. The little stationery store and the nearby tobacco shop were still tightly closed, and the Jewish greengrocer was unloading baskets of produce with his customary broad smile.

"Good morning, Herr Blumenrot, and how's it going?" Herr Bloch greeted him as he did every morning.

"And a very good morning to you", replied Blumenrot, rubbing his hands. "Hard times we're having, troubled times... You probably read the paper already. Do you think I should go to the market today? There's something scary in the air..." and he laughed as if he'd made a great joke.

A few more steps, and Herr Bloch heard the rattling of the milk cans stacked on the horse-drawn wagon of Blaufuchs, the Jewish milkman, a perpetually grouchy fellow, who was mumbling something into his beard as he poured the milk in a steady stream from the tilted can into the customers' waiting pot. Were his mutterings a commentary upon the difficult conditions, or the beginning phrases of the morning prayer? One could not tell.

All around Herr Bloch, the town went about its usual activities — delivery boys sped by on their bicycles, carrying orders from the butchers and bakers; girls and women on their way to work in the factories jumped out of their way, throwing smiles and jokes at the nimble messengers. Trolley cars, still with their lights on, braked noisily while cars and trucks tooted their horns. It was the usual morning clamor of the city, not different from any other day.

Yet, there was something in the air. But perhaps it was only Herr Bloch's imagination? It seemed to him that he was still under the spell of last night's oppressive dreams...

Suddenly, the strident siren of a fire engine broke into his thoughts, racing through the jumble of traffic, scattering pedestrians on all sides. Herr Bloch had reached the clock tower in the center of the city, whence the tree-lined Promenade led to the synagogue.

*

A Jewish shul burns on Kristallnacht

"Where ya going, Jew?" someone shouted at him. "Don'tcha know your synagogue is burning?"

"Yeah — that's a great bonfire you're having!" came another yell.

Herr Bloch ignored the sneering remarks; hundreds of years of anti-Semitism had taught the Jewish population to appear deaf and dumb in the face of the gentile jeers. He continued toward his goal, but a heavy iron chain barred his way. Errand boys, factory workers, and even policeman stood by, idly watching the show, while more fire engines raced past from every direction.

Now Herr Bloch saw thick columns of smoke ascending from the dome, and drifting toward the Promenade, with solitary sparks glittering like jewels against blackness. No one seemed to be concerned with him, but it was impossible to go any further.

Herr Bloch glimpsed the two "early birds" of the congregation leaving the scene; although they were old friends, and were walking next to each other, not a word was exchanged. When he hailed them, they did not reply. Quickly, he turned and began to make his way back, meeting others silently hastening away from the conflagration.

A solidly well-dressed woman spoke to him: "Nice times we're having, eh? So they're burning the synagogues now! Just because one man got killed over there by a crazy fellow, they want to kill everyone!"

Salo Bloch did not reply. She waited until he had opened his front door and gone in. "May G-d be with you!" she called out. He had never met her before, nor did he ever see her again...

*

Herr Bloch woke his wife and children. "When it's burning", he told them calmly, "it's better to get up."

"Where's the fire?"

"Everywhere! There's something evil in the air. May G-d be with us!" Almost mechanically he repeated the last words of the unknown woman. He did not want to mention the worst of all, the burning synagogue.

Outside, the dawn had turned into full daylight. Traffic in the streets had increased, and masses of office workers and businessmen crowded the sidewalks. And still, fire engines rushed through the streets; police cars, one after another, seemingly without any order or direction, passed by the flaming edifice as if it were invisible.

Herr Bloch went to the telephone to call some friends. There was no answer to most of his attempts; occasionally some distraught, inarticulate voices whispered a few words, and fell silent. Only sobs were heard at his next try.

"Where is your husband?" he asked.

"Where all the men of the Jewish council are today — they came for him!" And quickly, frightened of the information that had been given, the telephone was hung up.

The coffeepot stood steaming on the table as always; the little rolls in their basket, the jam in its porcelain dish — all was as usual. Only the butter was missing — there hadn't been any for a long time. But no one felt like eating.

Now came a new disturbance. "No school today! Hooray! They told us to go home! Hooray!" Children's feet came pounding up the steps, their voices full of excitement and joy at this unexpected freedom.

The pale faces around the table stared at each other. "What's going to happen now?"

Nevertheless, Herr Bloch picked up his briefcase as he did every morning, and, out of long habit, made ready to go to work. "You'd better take a taxi today," his wife called out. The telephone rang. It was the manager, calling from the office, announcing that, by police order, all Jewish businesses were to remain closed. "And don't worry — the bookkeeper will bring the mail to your house."

*

Salo Bloch searched through his papers and took out the family's passports. He had arrived in this German city more than thirty years ago, and had been quite successful, even honored; yet, he had kept his Swiss citizenship out of love for the country, its mountains and people. A sign which he had prepared years ago, certifying that the house was under the protection of the Swiss consulate, went up on the outside wall.

The doorbell rang, sharp and loud. What now? But it was only the mailman, a small friendly person who came up the steps to claim the foreign stamps for his collection.

Again a ring, but softer now, more careful: some friends had come at this unaccustomed hour and, slightly embarrassed, refused an offer of refreshments. They had been up early and had already eaten, they said. From behind the blinds, they could see that the few Jewish shops were closed and locked tightly. The fruit man was hurriedly turning the key in the door, as if it were Friday afternoon.

On both corners, agitated groups gathered in excited debate, but in between, the street lay deserted. Only the occasional ringing of the trolley bells, the roaring of fire engines and the sirens of police cars broke the calm.

*

TRR! Crash! TRR! Suddenly a tremendous noise of shattering glass assaulted the ears of the terrified listeners. A furiously screaming mob was gathered on the sidewalk in front of the coffee house "Markreich," which had become the gathering place of the Jewish middle class when other establishments were closed to them. The owner was surrounded by young thugs who ordered him to break his own windows with an iron bar. "Harder! Faster! More, more!" they shrieked, as his arm swung again and again, as if controlled by some outside power.

"Get rid of that Jewish swill! The side window now — come on! Harder! Faster!" The crowd shouted with joy as snow-white cream poured onto the sidewalk, with pieces of cakes and pastries swimming in the thick liquid. "Again! Again!"

Policeman dashed by, ignoring the disturbance. A guard appeared and politely requested, "Please — no gathering here, no standing..." No one listened, and the guardian of the peace didn't seem to care at all.

Pogrom! For the first time, the dreadful word came to the lips of Herr Bloch and his fellow spectators. Kishinev, Chmelnicki, Petliura, Denekin — all those places and people somewhere in far- off Russia. The distant bloody images came to life, moved ever nearer and nearer.

"Close the shutters and gates!" Or, perhaps, better not — it might only incite the mob more and serve as identification of the terrified Jewish prisoners within. Orders and counterorders contradicted each other.

"No one is to stand at the window!" "No one outside!" "Isn't that someone calling for help?" "Isn't that blood flowing over there?"

No, it was not blood, but a heap of ripe tomatoes which had been thrown out of Blumenrot's shop, and trampled into the gutter, mixed with apples, heads of cabbage, onions and beets. "A typical Jewish dish," someone called out, and the bystanders howled with laughter.

Now a stream of white mingled with the varicolored mess; rivers of milk came pouring out of Blaufuchs' dairy store, whose cans were emptied to the last drop onto the dusty sidewalk, eventually joining the ruined produce in the gutter.

Blumenrot wrung his hands. What had he ever done to deserve this? Whom had he ever harmed? He strictly adhered to all the laws, observed the Sabbath, did not fool or cheat anyone, and had friendly relations with everyone, including non-Jews.

Why? What did they want from him?

And his poor customers, who'd have nothing to eat today! No fruit, no vegetables, nothing! There were such shortages anyway — how would they ever manage? Blumenrot loved his customers, far more than was warranted by his small profits. A nervous twitch pulled his features into a grimace which could be mistaken for a smile.

"Look at that Jew grinning, making fun of us!" The angry words were followed by a wild blow, and Blumenrot lay sprawled in the gutter, among his smashed vegetables. "Now clean it up, Jew. Clean up every bit of that mess, and do it fast!"

Blumenrot obeyed in silence, his face never losing its customary expression of benign amusement.

Next door, books, papers, fountain pens, copy books and slates were hurled from the stationer's into the road. "The Talmud!" the crowd screamed as a thick volume hit the cobblestones. "Let's make a fire and burn the Talmud!"

But a secret dread held them back. Instead, the windows were broken with a few quick blows, and more and more books went sailing into the filthy street.

Weinheimer, the owner of the small shop, was a great Talmudic scholar who used the many quiet hours in the store for his deep research into all the paths of the Torah. Just last night, in the pre-dawn hours, he had awakened his wife with the joyous cry, "Rivkah, I've got it!", having found an answer which reconciled all the contradictions he had found in the portion he was studying.

This morning he had been on the way to prayers, carrying his tallis bag as usual, when he realized that it was impossible to go on. So he had donned his tallis and tefillin in a room adjacent to his store, and had begun the morning prayer with intense concentration. The screaming mob dragged him outside, still clad in his prayer vestments. "Hey, look at St. Paul!"

"Nah, he's Judas! He'll get his false kiss back right now!" The crowd howled and jeered, and fists were raised, but, "Don't touch him! Let his collect all his junk — fast! Hurry up, Jew! get your papers and Talmud rags together!"

And now Weinheimer lay stretched out in the gutter and, with his delicate scholar's hands scraped up splinters of glass, shreds of paper and torn books. His neat gray beard swept the ground like a broom. The crowd went wild with excitement. "What a show! Just look at him! That'll teach him to kill our Lord!"

Weinheimer seemed not to hear or see the mob. His lips moved silently, "Rivkah, I've got it!" His eyes closed and he continued to work mechanically. He had probably been in the middle of the "Shema" when they dragged him out into the street, and he had to start from the beginning now...

This is how the Jewish martyrs of ancient Rome must have appeared when they entered the arena clad in their white prayer shawls to do battle with wild animals...

An elderly gentleman with a gray goatee and the dignified air of an academician or clergyman passed by, observing with disquiet the white-clad figure cowering in the gutter, and the mocking rabble pressing closer. "And you dare to call yourselves decent Germans!" he murmured.

"Jew servant!" came the instant reply, along with threatening words and raised fists causing the passerby to turn rather quickly into a side street, and to continue on his way at top speed.

End of Part I

|